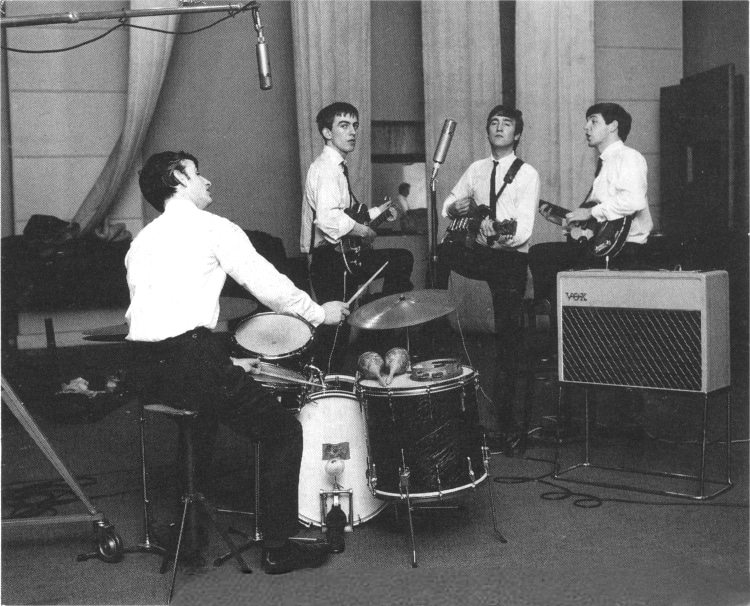

Returning to Studio 2, September 11, 1962

The Beatles were brought back into the studio on September 11, 1962 and began with P.S. I Love You . After completing what would become the B-side to Love Me Do, they returned to Love Me Do, tracking the song at least 18 times until they were satisfied (take 5 was chosen for the master1). With an hour left in the session2, they ended with the first takes of Please Please Me.

According to The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Ron Richards was their producer this day with George Martin unable to be there that morning. Ron had a working relationship with drummer Andy White, so he booked the session with White on drums. White appeared on several charting albums at the time. They weren’t completely happy with Ringo Starr‘s performance on September 4.3 4

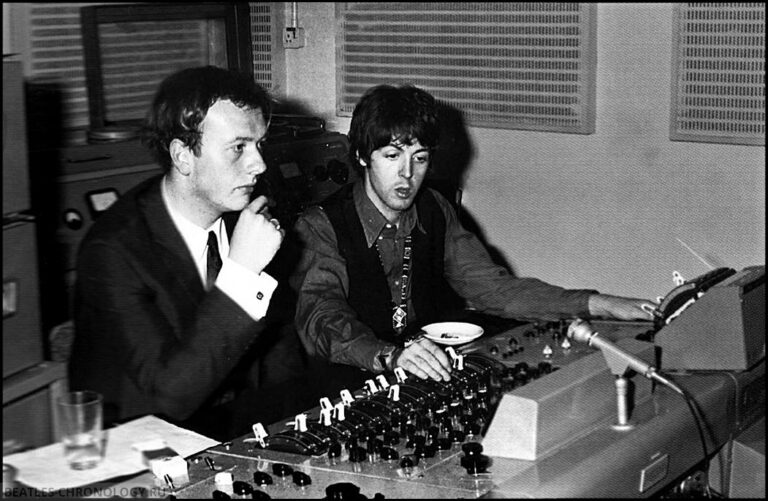

Author and Beatles aficionado Mark Lewisohn shares a quote from Ron Richards on that day concerning Ringo’s attitude and maturity about being replaced by White.

He just sat there in the control box, next to me. Then I asked him to play maraca on ‘P.S. I Love You’. Ringo is lovely – always easy going. ‘What do you want me to do? I’ll do it. You don’t want me to do anything? Good.’5

Geoff Emerick provided a more accurate observation:

Following some discussion, it was decided that full drums weren’t necessary on the song and he was relegated to playing bongos. After a few run-throughs, Ron suggested that Ringo go downstairs and join in, playing maracas. I could sense that he was growing increasingly uncomfortable at having the sulking drummer sitting beside him, and this must have struck him as a good way of getting Ringo out of the control room.6

David Bedford of Brightmoon Liverpool explains the dynamics at play in this insightful video.

From the EMI REDD.37 to the Final Mix

The REDD.37 recording console allowed for eight inputs and four outputs. So at most, engineers could mic four instruments during each take. Engineers mixed the output of the REDD.37 down in mono to the BTR-2 tape machine on 1/4 inch tape. And so we immediately see commitments and decisions with the mix being made.

According to the manual below, the suggested setup was this:

For stereo purposes, the uses allotted to the four tracks are determined by the fact that one of the main design aims of the equipment is that it should produce a tape from which both the stereo and mono master tapes can be made. Consequently, anything which detracts from the likelihood of doing this must be rejected. With the main stereo tracks on the outside edges of a 1″ tape, there would be a grave danger of the high frequency signals becoming out of phase due to “weaving of the tape. It was therefore decided that the convention will be:

Track I:- Main stereo left.

Track II:- Main stereo right.

Track III:- Auxiliary left.

Mono injection (towards left of applicable).

Track IV:- Auxiliary right.

Mono injection (towards right if applicable).

Tracking and Mixing

The Beatles would track the instruments first: guitar, acoustic guitar, bass, drums – live as a group. While they performed, the instruments were live mixed on the REDD.37 valve mixing console. Engineers set levels and EQ to balance the track in the mix. From there, the mixed signal was recorded to Tape Machine A (usually a BTR-2 or BTR-3) in mono or twin-track, depending on the session.

To add vocals or additional elements (in this case vocals, handclaps, and harmonica), the instrumental tape was played back on Machine A, while the new parts were performed live in sync and captured together onto Machine B, in a process known as superimposition or sound-on-sound bouncing. This led to more sophisticated multitracking techniques later.

The result was a new mono composite tape that combined the original instruments with the newly added vocals or effects. Each generation added more layers but also a slight degradation in fidelity.

The band would perform the songs anywhere from five to eighteen takes while tracking what would become Please Please Me. As the band continued working on their debut album, the number of takes they took on each song declined. This shows an increase in their confidence and skills.

Comping

When necessary, engineers spliced (physically cut the magnetic tape) the best segments of each take. They then compiled the tape together to form the complete song. Today, engineers call this comping (short for compiling). In order to do this, drums had to be very consistent, otherwise you would have slight variations in timing. Artists now record with a click track (metronome) in their headphones, but not in 1962.

The master was mixed in mono (even if twin-track was used as an intermediate step). It was then recorded onto a lacquer disc immediately after the recording session was completed. This process took roughly an hour, reinforcing their decisive approach.

Above is the manual for EMI REDD.M37. The REDD.M37 was a mobile adaptation of the REDD.37 console, maintaining the same circuitry within a more portable chassis. Note that the mobile REDD.37 weighed 750 lbs.

As artists, we are sometimes crippled by an abundance of options. We can add sixty layers if we wish, but how do we know which take to select when we save everything? We can get lost within our own lack of decisiveness. This leads us to the first element to learn from, which is: Be decisive.

It was with the REDD.37 console that The Beatle’s full-lengths Please Please Me, With the Beatles, A Hard Days Night, Beatles For Sale and singles (1962–mid 1964) were recorded.

Mono vs Stereo

When you listen to the stereo release of Please Please Me you can bass, guitar, handclaps, and drums on the left, and John Lennon and Paul McCartney, guitars, and drums on the right. The drums sitting in both sides pulls the two together. But you can hear the stereo width is quite spread hard left and right. This is all due to the limitations of the cutting-edge equipment they were working with.

At first these albums were released in mono (you’ll notice that everything sits in the middle). At this time stereo was an afterthought as most consumers had mono record players, mono radios, and mono format was standard for pop music. Most artists and producers weren’t very interested in stereo mixes in 1962. Stereo would catch on in the 1960s and so stereo versions of these albums were later release.

You might notice on the stereo release of Please Please Me the songs Love Me Do and P.S. I Love You, are mono mixes… the first two songs they completed in the studio on September 11. Later remasters and reissues of these songs offered stereo versions.

Please Please Me single

The Beatles were brought back into the studio on November 26 to record their second single, Please Please Me as an A-side, and Ask Me Why, as the B-side. After completing the Please Please Me single, George Martin jumped on the talkback mic. “Boys, you’ve just made a number one record!“, Geoff Emerick recalls him saying.“7

Please Please Me would reach No. 2 on Record Retailer chart, the precursor to the UK’s official chart, and No. 1 elsewhere.8 Martin would bring the band in on February 11, 1963 and the band would record eleven songs in a twelve hour session to complete the album… an astonishing feat!

Working within Constraints

Throughout the Beatles recording experiences the band, producers, and EMI’s engineers were working within constraints. While we have seemingly unlimited tracks that can be quickly added in our DAWS, such as Pro Tools or Logic Pro, they were initially limited to what the mono BTR-2 and twin-track BTR-3 tape machines would allow. These limitations forced them to find creative ways to work that was concise and decisive.

The constraints many of us have today is in the limitations of our budgets. And so we learn how to utilize what we have, borrowing from friends when necessary. We are also limited by our experience and knowledge. But when we set constraints on our recording process, we are less likely to get mired in the muck of having too many layers and takes to mix later. But when we embrace them, constraints often spark creativity.

The Beatles walked into the cutting edge of recording equipment. They had engineers who knew their equipment well enough to improvise and push the limitations. We see this in the stories shared in our Mix Note Superimposition: How Do You Do It?

Be Decisive

As you’re working through a project, whether you’re recording a song layer by layer or tracking as a live band, be decisive. Make decisions as you traverse the creative process. The more you push off to decide later, the less likely you’ll get the best result.

The Beatles and the team around them had to quickly decide what to keep and what to cut. There were only a select number of superimpositions (overdubs) they could do, every time the process being destructive.

They were intentional in setting EQ and compression as they recorded. When they balanced signals and EQ, they were unable to go back to fix things. Everything they did during the recording session was final. The option to fix it in the mix was not afforded to them. Intentionality and decisiveness was a necessary discipline of an engineer.

Jerry Hammack in The Beatles Recording Techniques writes about balance and intentionality:

If you listen carefully, nearly every performance in a Beatles song can be delineated one from the other. You can hear Lennon’s and Harrison’s individual guitars. You can hear McCartney’s bass and Starr’s drums. The Engineers were careful during recording to be certain each signal recorded was audible on tape when put up against the other signals present.9

Intentional Track Limitation

One way we can force ourselves to be decisive is to intentionally limit the number of tracks we’ll allow. While this decision can be easily ignored as we go along, placing a limit makes the creative process more exciting and challenging. This helps us avoid over stacking songs with endless layers where a simplified blend might serve better by allowing more space for the elements to develop their sound. Remember that the more you keep, the more you have to edit later.

Push Against Limitations While Honoring Them

Place limitations but then push against them. Instead of ignoring the imposed limitations, honor and recognize them… and find ways to innovate. We see balance engineer Norman Smith doing this by finding ways to bounce tracks while overdubbing, working with 1/4″ tape.

We will later find Geoff Emerick pushing against the limitations by creating effects or moving microphones closer to the source. In future Mix Notes, we’ll explore the different outboard gear and technique, such as ADT (Artificial Double Tracking) that they used, chamber rooms, and signal chains.

Suggested Exercises

- Limit Your Tracks: Start a new recording session and restrict yourself to four tracks only. Use one track for drums or rhythm, one for bass, one for melody (guitar, piano, or other instruments), and one for vocals. This exercise will push you to make clear decisions about instrumentation, arrangement, and balance early in the process.

- Record Without Overdubs: Set up a live session where all parts—rhythm, lead, and vocals—are captured in a single take. Focus on getting the right balance of volume and tone directly from the performance. By skipping overdubs and relying on a live mix, you’ll learn to prioritize strong initial takes and become more decisive in shaping the overall sound.

- Recreate a Mono Mix: Pick one of your previous songs that has multiple layers and try mixing it down to a single mono track. Work with EQ, panning (to the extent possible), and dynamics to ensure all elements can be clearly heard. This exercise will teach you how to make critical mix decisions and build a cohesive sound without the reliance on stereo width.

- While it’s widely reported that take 18 was the final take recorded for Love Me Do, the actual master released in 1962 was indeed taken from earlier sessions with Ringo on drums (often referred to as the “Ringo version”). The version from September 11 with Andy White drumming, although extensively recorded that day, became more prominent in later pressings and releases. ↩︎

- Geoff Emerick wrote in his book: “The superimposition took only a single run-through, and it was only noon—two songs had been completed in just two hours—so there was still another hour of time available to the Beatles.” ↩︎

- The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions ↩︎

- At the time of the September 11, 1962, session, Ringo Starr had only recently joined The Beatles, having replaced original drummer Pete Best in mid-August. Producer George Martin, initially hesitant about Ringo’s abilities due to his limited experience with the band, decided to bring in session drummer Andy White for the recording. This decision stemmed not from a lack of faith in Ringo’s talent but rather from a desire for the session to run smoothly and produce a polished final product. Ringo, known for his laid-back demeanor, reportedly took the situation in stride, demonstrating a cooperative attitude that would later become one of his trademarks. Over time, his consistent and inventive drumming style proved essential to the group’s sound, solidifying his place as a key member of The Beatles. ↩︎

- The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions ↩︎

- Here There Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles ↩︎

- Here There Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles ↩︎

- All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release ↩︎

- The Beatles’ Recording Techniques: Recreating The Classic EMI Recording Studios Sound In Your Home Studio ↩︎