Introduction

The EMI BTR-2 was one of the most important tape machines in post World War Two recording history. Famous for its use in early Beatles recordings and EMI’s duplication rooms, the BTR-2 was both an improvement and an innovative step forward from the heavy mechanical designs of earlier magnetic recorders.

Its partnership with mixing consoles like the REDD.37 defined an entire era of recording. While the Studer J37 has since become infamous with recording engineers, information surrounding the BTR-2 is scant and difficult to pull together. This article aims to bring these scattered details to one piece.

Before the BTR-2: A Step Forward from the BTR-1

The BTR-1 (British Tape Recorder 1) was EMI’s first magnetic tape recorder, introduced around 1948. It evolved from steel and paper tape technologies and borrowed design ideas from captured German AEG Magnetophon recorders. The technology was largely gained from reverse-engineering these German machines.

However, the BTR-1 had several limitations:

| Feature | BTR-1 (1948) | BTR-2 (1952–1960) |

|---|---|---|

| Head Material | Steel erase heads (low frequency response) | Improved magnetic heads (higher fidelity) |

| Braking System | Manual cables (similar to bicycle brakes) | Electronic solenoid braking |

| Motor Layout | Motors at bottom, long drive shafts | Optimized for smoother operation |

| Tape Handling | Manual tensioners, strobe light for speed checking | More reliable tape tension, better tape path |

| Construction Style | Heavy, mechanical, very spacious | More compact, streamlined for studios |

| Electronics | Larger early valve design (e.g., KT66 tubes) | Improved bias and amplification stages |

Origins and Context of the BTR-2

EMI introduced the BTR-2 around 1952, and it was manufactured until about 1960. The BTR-2 modernized nearly every aspect, introducing electronic switching, solenoid controls, and improved audio fidelity.

It was designed primarily for monophonic recording, during a time when stereo was just emerging. 1 While it borrowed from the BTR-1 (and indirectly the AEG Magnetophon), the BTR-2 was a clean-sheet design, and was a brilliant product of British independent innovation.

BBC Radio leaned heavily on the BTR-2 and purchased around 750 units, making them the standard recorder for radio production. David Hughes of BBC Radio described the BTR-2 in 1954 as, “this was a Rolls Royce of recorders.” He wrote:

I was able to attend many of the recording sessions, usually in a sound radio music studio – Aeolian Hall, Maida Vale 3 and the like. Here I came across the BTR again, by now ‘old stagers’ in these studios and presided over by a fine breed of chaps called ‘XP Operators’ (XP meaning transportable and referring to the tape machine, not the operator!). Real experts they were: fast and accurate editors. I was often able to walk away from the session with a fully leadered tape under my arm, together with the precautionary ‘dupe’. 2

Paired with early EMI mixing consoles, like the Type 17 and later the REDD.37, the BTR-2 became the heart of EMI’s recording process. And thus, it helped shape the sound of the early Beatles recordings.

Technical Characteristics

The BTR-2 supported 15 ips and 30 ips operation (ips is short for inches per second). It’s important to note that EMI studios tracked at 15 ips. 3

Early machines used a reverse head block configuration. Later upgrades included butterfly-style heads to prepare for stereo recording.

According to Recording the Beatles, the BTR-2’s tape transport was known for its mechanical stability, which made it well-suited to the long takes and analog tape effects employed in the early 1960s. 4

Some BTR-2 machines were later designated BTR-2AM, reflecting custom amplifier modifications made for studio-specific needs. These machines maintained the core transport design but incorporated upgraded replay circuits, metering changes, and improved bias handling. 5 Similar modifications happened with BTR-3 units later too (e.g., BTR-3AM). 6

- The max reel size was 10.5”

- 3 tape heads: erase, record, and playback heads

- 3 motors: 1 capstan, 2 spool motors

- No auto reverse capabilities

- Standard UK/European studio voltage: 220–240v

- Frequency Response at 15 ips: 50Hz–15kHz within ±2dB

- Wow and Flutter: ≤0.15%

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: ≥58dB

Tape Evolution at EMI: From H50 to H77

In the 1950s, most BTR-2 machines at EMI and the BBC recorded onto H50 tape, which used paper or acetate bases. These early tapes had inconsistent performance, requiring engineers to manually align the bias and recording level for each reel.

By 1960, EMI had developed H77 tape, using a PVC base and offering about 4dB better signal-to-noise performance. The greater consistency of H77 allowed standard machine settings to be used, improving session efficiency and reducing setup complexity. 9

This quiet revolution in tape quality paralleled the broader technical evolution that the BTR-2 itself helped pioneer.

The BBC began using magnetic tape for audio recor!ling on a routine basis in 1952, following a period of experiment and development. In the space of the next five years tape almost completely displaced the disc as the recording medium. Early tapes were manufactured by EMI, Kodak and Kramer (a Canadian Company). The equipment installed in most of the recording channels in the 1950’s was the EMI BTR2 tape recorder and most of the tape used was H50 made by EMI.

Early tapes with paper or acetate bases, had a certain amount of variation in the quality and performance due to variations in the size of the oxide granules and the thickness with which it

was laid on the tape. 10

Remote Control Integration

By 1962, many BTR-2 machines — especially those used in professional studio and broadcast environments – had been fitted with remote control systems.

This allowed engineers to start and stop machines from the studio mixing desk after arming them in Remote mode. In fast-moving recording environments, this system enabled precisely timed tape starts and live inserts, with no need for engineers to leave the desk.

Larger facilities even implemented centralized recording rooms where engineers supervised multiple remote-controlled machines from a distance.

The BTR-2’s remote capabilities made it a highly integrated part of EMI’s and the BBC’s evolving recording workflows. 11

EMI’s REDD.37 desk had routing and cue systems compatible with remote-start logic. Engineers could monitor or mix stereo and mono simultaneously — including starting multiple decks with precise timing (e.g., during bounce-downs or live mono captures).

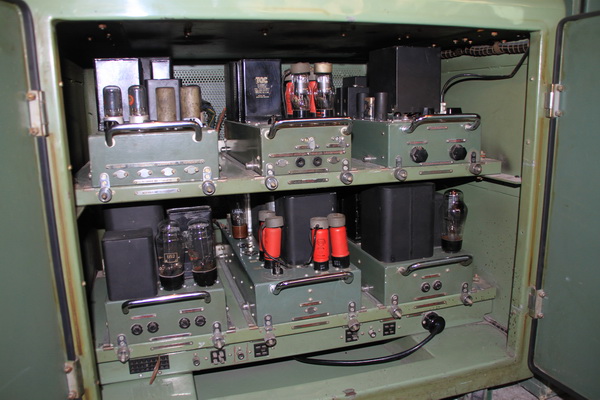

Amplifiers and Electronics

Original BTR-2s featured large octal valve (tube) units, 8-pin mounts. The amplifier relied on two KTW63 vari-mu pentodes, “arranged in cascade to give the long logarithmic range” as David Hughes recalls. 12

Some later units (especially studio-modified ones) included Redd.18 replay modules to improve headroom, though this was not specific to Abbey Road. 13

BBC later rebuilt many BTR-2s into RD4/4 units, adding stereo head blocks and transistorizing electronics for better long-term reliability.

David Hughes added,“The BTR/3 looked on the exterior very much like its senior. Inside was neat shelf of plug-in miniature valve units instead of the octal ‘blockbusters’.” 14

1957: The REDD.18 Replay Upgrade

As magnetic tape recording advanced in the mid-1950s, EMI engineers realized that the original BTR-2 replay amplifiers couldn’t meet the rising standards for fidelity and dynamic range. In 1957, the REDD.18 replay modules were introduced across studio BTR-2 machines, replacing older valve circuits.

These upgraded amplifiers dramatically improved headroom, noise performance, and signal stability, making the BTR-2 viable for increasingly sophisticated stereo and high-fidelity mono recording.

Meters and Controls

Most studio-installed BTR-2s came with white-faced Peak Program Meters (PPM), a BBC standard that EMI also adopted for precision level monitoring. These meters measured dynamic peaks much faster than traditional VU meters, crucial for tape recording headroom management.

David Hughes recalls:

This was the full EMI commercial specification and notable for providing a full 40dB of range (the BBC unit, from time immemorial was only 26dB – for the good practical reason of easy reading and providing the efficient modulation of AM transmitters). 15

BBC sometimes customized meter panels – some transportables or RD4/4 rebuilds used simplified meters. When rebuilt into RD4/4 stereo units (BBC modifications), original white PPMs were sometimes replaced with smaller BBC “in-house” meters. Around mid-1960s, as RD4/4 units were rebuilt, black-faced BBC meters started appearing (especially compact meters in mobile and stereo control units).

Transportable BTR-2s (BBC emergency units) might have had different or simplified meters, especially if modified later (e.g., during RD4/4 conversion).

Maintaining the BTR-2

Tape machines require maintenance, and the BTR-2 was no exception. Every morning engineers demagnetized the heads with a green mallet demagnetizer. They oiled the motors at regular intervals, and check for flutter from worn rubber couplings. Noise floor testing ensured background noise stayed below -60 dB.

Geoff Emerick as a button-pusher

The Beatles’ balance engineer Geoff Emerick started at EMI as an assistant engineer. This meant he managed tape machines during their recording sessions. In his autobiography Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles, he writes:

Because each machine ran on its own mechanical clock, I had to manually log all the clock timings for each take on every tape box, as well as jot down any relevant notes. I also had to be constantly aware of how much tape was left and judge when it was going to run out.

Then there was the physical labor of constantly changing four reels of tape. There was no backing plate, so sometimes the tape would literally start to rise up over the guideposts and fly off the machine while you were trying to spool it back as fast as you could—musicians were standing by, and time was money. You had to be very organized, and you could get into real trouble if you developed a mental block—they might want a playback of take 39 one minute, then decide to record take 62 on a completely different reel of tape, all on four separate machines. 16

Special Versions and Custom Modifications

In practice, a large proportion of BTR-2 machines, especially those used by the BBC, were modified during their working lives. Modifications were made for stereo compatibility, transistorized replay circuits, transport upgrades, or field portability. Original, unmodified BTR-2s are now extremely rare.

Other special versions or modifications include:

- Portable Units: Two-box transportable BTR-2s were used for deferred BBC facilities and mobile emergency sites.

- Hybrid Machines: Some BTR-2s were modified with BTR-3 front panels but kept BTR-2 electronics.

- Master Dub Machines: Units capable of both recording and replay served as master dub decks in EMI’s duplication rooms.

Some surviving BTR-2 machines from Abbey Road have toggle switches instead of rotary.

The RD4/4: BBC’s Stereo Adaptation of the BTR-2

As broadcasting transitioned from mono to stereo in the 1960s, the BBC faced a challenge: how to adapt the many BTR-2 machines already in service? BBC needed to modify machines to meet new stereo requirements without immediately replacing them.

Their solution was characteristically ingenious: the RD4/4. It retained the BTR-2’s mechanically robust tape transport. They added stereo head blocks capable of simultaneous left/right recording and playback. Tape speed control was tightened, although minor issues like azimuth drift remained a problem for these aging transports.

The internal electronics were heavily modified. The original valve-based (tube) replay and record amplifiers were replaced with custom BBC transistor modules. New stereo circuitry allowed engineers to mix, monitor, and adjust stereo signals independently.

These BBC modifications often combined EMI designs with in-house engineering solutions to extend the life of the monophonic BTR-2 into the stereo era.

The RD4/4 effectively extended the working life of the BTR-2 by another decade, allowing the BBC to meet the growing demands of stereo FM broadcasting and stereo television pilots without the immediate expense of buying entirely new machines.

David Hughes adds:

An adjunct to the BTR/2 (and RD4/4) was the ‘Ear’ or ‘Outrider’ or ‘Compiler’ as I think they were officially named. This small unit (in EMI green of course) bolted on to the side of a machine and provided an extra spooling platform driven by a normal spooling motor. This was energised with AC for drive, or 36V DC for magnetic braking. A simple switch on the side of the unit gave ‘spool’, ‘brake’ or ‘off’. 17

BTR-2 and RD4/4 units remained in service within BBC well into the 1980s.

The BTR-2 in the Studio: REDD.37 Integration

By the late 1950s, BTR-2 tape machines were paired with the newly introduced REDD.37 console. The REDD.37’s careful track assignments 18 matched the BTR-2’s layout:

- Track I: Main stereo left

- Track II: Main stereo right

- Track III and IV: Auxiliary mono or overdubs

According to The Beatles Recording Techniques, EMI often ran parallel recording paths, routing REDD.37 console outputs simultaneously to a twin-track BTR-3 and a mono BTR-2. These Delta-Mono setups allowed engineers to produce real-time mono mixes while capturing a stereo version, with the BTR-2 frequently serving as the official mono master deck well into 1963. 19

Jerry Hammack elaborates in The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 1:

At times during this period, tracks were simultaneously recorded to both twin-track and mono. For this purpose, inputs to the REDD console were split-routed to a ‘Delta-Mono’ control bay that allowed an alternative mix to be created. For such sessions, the BTR-2 and BTR-3 are both considered to be primary tracking machines… 20

The typical Abbey Road studio workflow looked like this:

Microphones → REDD.37 mic preamps → REDD.37 main faders and routing → Line Output → BTR-2 tape machine.

The combination of BTR-2 and REDD.37 ensured that EMI’s early stereo and multi-microphone recordings could be balanced cleanly in post-production without losing signal quality.

Tape Echo and the BTR-2

EMI’s early tape echo system, known as S.T.E.E.D. (Send Tape Echo / Echo Delay), relied on routing audio signals through a BTR-2 to generate delay effects. The delayed signal was returned to the console and mixed with the original, producing real-time echo during recording or mixdown. 21

In some cases, engineers fed the output back into the machine to create repeat echo effects — an essential part of early rock ‘n’ roll recordings. This technique was used not only for vocals, but occasionally to thicken reverbs applied to chamber returns as well.

“A colleague of mine was at Abbey Road in the late 1950s and was instrumental in using tape echo with a BTR/2 running at variable speed, one of Cliff Richard’s records was the first use it,” reflects David Hughes. 22

The BTR-2 at Abbey Road

BTR-2 tape machines were a key part of the recording chain at EMI Studios (Abbey Road) while The Beatles worked on their early albums. By 1964, the BTR-3 had become the primary 4-track recorder at EMI Abbey Road. At this point, the BTR-2 was no longer used for tracking, but was still used for mono mixdowns and tape echo into the mid-1960s. EMI continued to use the BTR-2 for duplication purposes.

Working in tandem with early EMI mixing consoles and later with the REDD.37, the BTR-2 delivered the warmth and immediacy that defined the Beatles’ early sound.

Even as 4-track technology expanded, the BTR-2 remained the silent witness to the birth of a musical revolution. Studio documentation from the period shows that full 4-track recording only became routine at EMI later in 1963, further supporting the BTR-2’s central role in capturing the Beatles’ earliest commercial releases.

Transition Years: BTR-2 and BTR-3 Together

During the early 1960s, EMI Studios often ran BTR-2 and BTR-3 tape machines side-by-side.

The newer BTR-3 handled 4-track recording, while the BTR-2 remained trusted for mono recording, editing, and safety backups.

Many early Beatles recordings captured on 4-track tape were mixed down to mono using BTR-2 machines for final release, preserving the warmth and familiarity listeners associated with EMI’s classic sound.

EMI Tape Machine Timeline (1948–1970)

Closing Thoughts

We cannot overstate how foundational the BTR-2 was for tape machines. It established standards for what a professional studio tape machine should be. Yet it remains a quiet presence in recording history, a machine that shaped the industry not through spectacle, but through stability, precision, and the trust it earned from those who used it daily. Its legacy lives on in the workflows it defined, the records it captured, and the engineers it trained, a silent backbone to a musical revolution.

Sources

YouTube videos

- The Rare EMI BTR-1 (British tape recorder 1) 1948 reel to reel

- EMI BTR-2 reel to reel

- EMI BTR-2 reel to reel tape recorder restoration projects

- The EMI BTR-2, could these have come from Abbey Road studios?

- Super rare EMI Hayes only reel to reel – BTR2/3 tape recorder

- EMI RD4/4 reel to reel tape recorder BBC mod from the EMI BTR-2

Footnotes

- Super rare EMI Hayes only reel to reel – BTR2/3 tape recorder ↩︎

- The EMI BTR/2 – A personal memory by David Hughes ↩︎

- Some transportables were limited to 7½ and 15 ips, but standard studio machines ran at 15 ips and 30 ips. ↩︎

- Recording the Beatles : The Studio Equipment and Techniques Used to Create Their Classic Albums by Kevin Ryan & Brian Kehew (2006)

This book is out of print and difficult to find. You can read a digital copy on Scribd. ↩︎ - EMI BTR-2 Overview — reel-reel.com (Historical summary and restoration notes) ↩︎

- BBC, EMI duplication rooms, and mastering facilities often requested small-batch modifications — that’s why so many surviving BTRs are unique inside. ↩︎

- EMI BTR-2 Overview — reel-reel.com (Historical summary and restoration notes) ↩︎

- Vintage Recorders: EMI BTR-2 ↩︎

- Type 200 Tape in ENG INF (summer 1982) ↩︎

- Type 200 Tape in ENG INF (summer 1982) ↩︎

- High-Quality Sound Production and Reproduction: BBC Programme Operations Training Manual by H Burrell Hadden ↩︎

- The EMI BTR/2 – A personal memory by David Hughes ↩︎

- Steve Hoffman Forums ↩︎

- The EMI BTR/2 – A personal memory by David Hughes ↩︎

- The EMI BTR/2 – A personal memory by David Hughes ↩︎

- Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles by Geoff Emerick ↩︎

- The EMI BTR/2 – A personal memory by David Hughes ↩︎

- REDD.M37 Reference Manual ↩︎

- The Beatles Recording Techniques by Jerry Hammack ↩︎

- The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 1 by Jerry Hammack ↩︎

- The Beatles Recording Techniques by Jerry Hammack ↩︎

- The EMI BTR/2 – A personal memory by David Hughes ↩︎