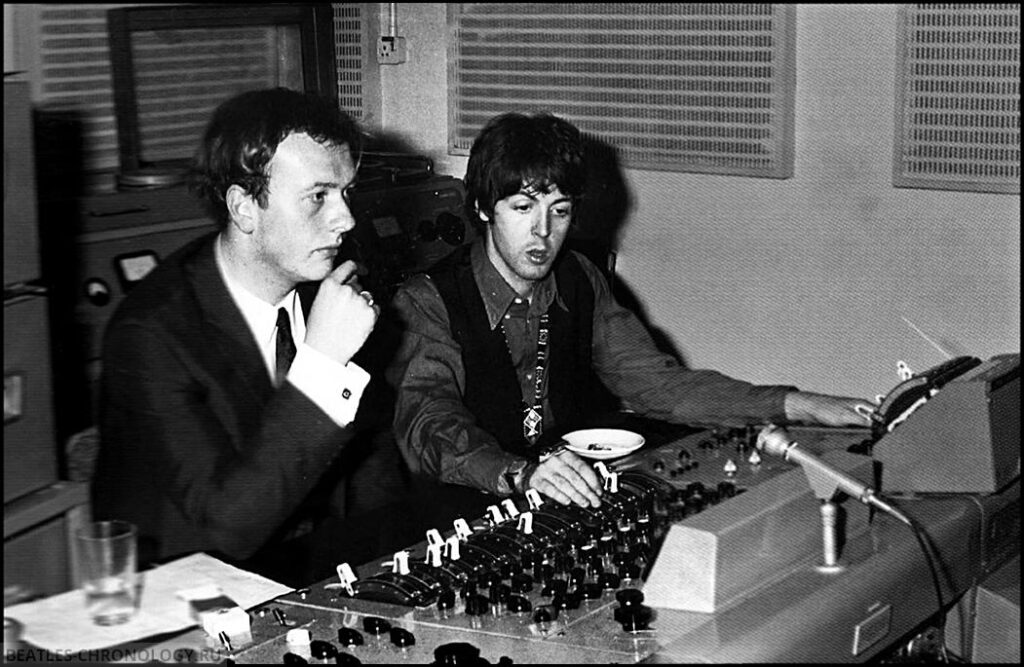

On September 3, 1962, sixteen year old Geoff Emerick arrived at EMI Studios for his first day of work. Fate would have it that coinciding this monumental day for Geoff and music history, the Beatles would record at EMI Studios, particularly Studio 2, for the first time. They had tracked there in June for an artist test.

Geoff observed the scruffy group with their strange haircuts as they stepped behind microphones to record How Do You Do It? He recalls the initial excitement at EMI in his autobiography Here There Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles:

Apparently there was quite a buzz around the studio about them, as much for their unorthodox personalities and cheeky attitude as for their musical abilities. Clearly, they were viewed by the staff as one of EMI’s top up-and-coming bands, and everyone was interested in seeing whether George and Norman could coax some hits out of them.1

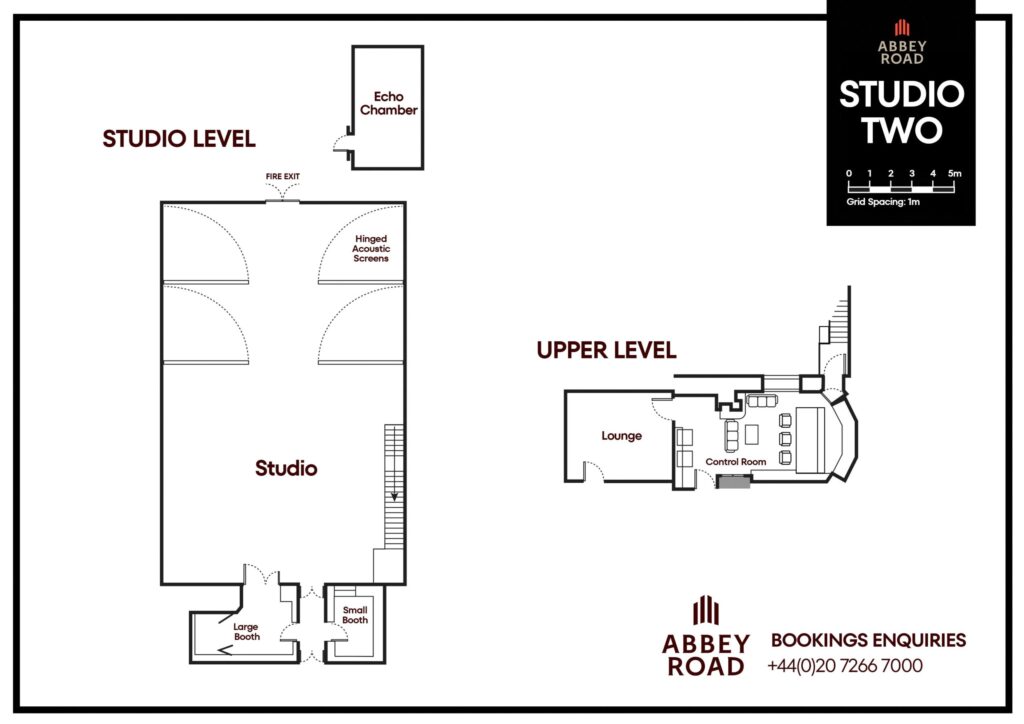

Recording in Studio 2

Studio 2 was unusual because it had the control room on the second floor, looking down into the studio room. From the upper-level control room, Geoff occasionally peered down into the live room below, observing both the band, George Martin and the engineers at work.

At EMI during this time, microphones, cables and signal chains were set up prior to a session by Maintenance Engineers wearing white coats. Naturally, EMI wanted to protect their large investment in microphones and other gear. Emerick would later change this by personally moving mics, bringing them closer to the source. Recording a massively successful band allowed him the room to alter techniques to form common practices today.

And so we begin with Geoff’s first role at EMI, Assistant Engineer, a button pusher where he managed the tape machines. At this time EMI utilized the mono EMI BTR-2 and twin-track BTR-3 tape machines. EMI had two four-track machines to share in their three studios, but “they were reserved solely for the use of established artists, not to be wasted on a new signing.” For this session, both the BTR-2 and BTR-3 machines were in use.2

Superimposition

They added hand claps after tracking How Do You Do It? by using a destructive overdub process called superimposition. Today, we can easily add another track and record it. But when you were recording with twin-track and mono machines, you had to be creative. Geoff explains this process:

Superimposition was the equivalent to the modern-day “overdub,” in which a new sound is added to an existing recording. Because the song had been recorded directly to a two-track tape (as opposed to four-track), the way this was accomplished was by loading a blank reel of tape on a second machine and putting it in record while the first machine played back, essentially making a copy of the original tape, along with the overdub.3

After recording How Do You Do It?, John Lennon told George Martin, “I have to tell you, we really think that song is crap. We want to record our own material, not some soft bit of fluff written by someone else.”4

Martin agreed to allow them to record one of their own songs, which led to them recording Love Me Do that day, recording 15 takes of the song. Also notable is that Ringo Star beat out Pete Best as the drummer. The Beatles would return to the studio four days later on September 11 to record the song for their full-length with Andy White on drums which you hear on their debut Please Please Me album.5 Their debut single, Love Me Do would become their first chart topping No. 1 song.

Superimposition Techniques in Your DAW

If you want to mimic Superimposition, know that this is a destructive technique. In other words, there’s no going back!

Superimposition worked by playing back the original track on one tape machine (Machine A), layering a live overdub, and recording the combined signal to a second machine (Machine B). This “bounced” take became the new master — a one-way process with no undo.

Machine A (plays original tape) –> + Live Overdub –> Mixed Together –> Machine B (records new composite tape).

Here are several options for achieving this technique:

Option 1: Commit-and-Print Overdubs (DAW)

- Bounce the mix of your existing take to a stereo track (or route it to a new stereo bus).

- Arm a second track to record.

- While playing back the original mix, perform your live overdub (instrument, vocal, sound effect).

- Record both to a new track — your superimpose take.

- Mute the original mix and overdub tracks — now you’re working only from the bounced version.

This mimics the commitment of tape superimposition, with no option to remix elements later.

Option 2: Use Tape Emulation and Re-recording

- Insert a tape plugin (see the list of plugins below) on your stereo mix bus.

- Set your DAW to record the bus output to a new stereo audio track.

- Add your overdub live or print it simultaneously as you’re recording.

- Now you’ve baked in the analog-style saturation and the overdub.

Use wow & flutter or bias/gain settings to really simulate the character of bouncing between tape machines.

Option 3: “Reamp-Inspired” Workflow

If you’re working hybrid (analog + digital):

- Play back your DAW stereo track into an outboard mixer or tape machine.

- Perform the overdub live into the mix.

- Capture the stereo output back into your DAW as a new superimposed take.

This is almost identical to Emerick’s tape-to-tape approach — you only keep the resulting mix, not the individual parts.

Emerick’s Innovative Legacy

Geoff Emerick’s early work with the Beatles didn’t just capture history — it helped shape the way we think about recording. Working with just two tracks, limited gear, and high expectations, engineers like Emerick found creative ways to solve problems. Superimposition wasn’t just a workaround — it was innovation born out of necessity.

Today, we have the luxury of infinite tracks and undo buttons, but there’s still value in understanding how these early techniques worked — and why they mattered. Embracing commitment, bouncing audio, and printing decisions can lead to more intentional mixes and a more human sound.

What started with a couple of tape machines and a button pusher in Studio Two became the foundation for modern music production. And the mindset behind it? Still just as relevant.

Plugins Emulating Tape Machines

Ampex ATR-102 Mastering Tape Recorder – legendary 2-track mastering deck, faithfully emulated by UAD for final mix polishing and analog depth.

AudioThing Reels – lo-fi tape textures, great if you want that colored, bouncy delay and vintage character (including Soviet-style machines).

FLYWHEEL Reel-To-Reel Tape – tone-focused reel-to-reel plugin by Fuse Audio Labs; adds analog saturation and compression with minimal fuss.

Kiive Audio Tape Face – rich, vibey emulation with adjustable wow, flutter, and saturation, perfect for creative tape layering and tone shaping.

Kramer Master Tape – Waves’ vintage tape plugin modeled after a rare 1/4” machine used by Eddie Kramer; warm, punchy, and musical.

Magnetite – Black Rooster Audio’s colorful, easy-to-use tape plugin with strong saturation, variable tape speed, and analog-style compression.

Oxide Tape Recorder – streamlined UAD tape plugin designed for instant analog warmth and tape saturation with minimal controls; great for quick workflow and subtle glue across buses or mixdowns.

Slate Digital Virtual Tape Machines (VTM) – meticulously modeled 2” 16-track and ½” stereo mastering tape machines; adds rich low-end, glue, and harmonic warmth with adjustable tape speed, bias, and noise—ideal for both tracking and mix bus applications.

Softube Tape – subtle analog warmth, with three distinct machine types and intuitive controls, great for superimposed textures and mix glue.

TAIP – modern AI-based tape emulation by Baby Audio; excels at lo-fi warmth, transient rounding, and creative tape effects.

Tape Machine 24 – part of IK Multimedia’s T-RackS series, modeled after a Studer A80; smooth, creamy sound with adjustable tape speed and formula.

TEAC A-6100 MKII – hardware deck known for high-fidelity stereo mastering; emulated or referenced in lo-fi tape chain plugins and samplers.

Waves J37 – modeled on Abbey Road’s tape machine, perfect for this kind of effect; includes adjustable bias, wow, flutter, and tape formulas. Part of the officially endorsed Abbey Road Collection.

Studer A800 Multichannel Tape Recorder – iconic 24-track tape machine used on countless major records; faithfully emulated by UAD and others for warm, musical multitrack saturation with adjustable calibration profiles and tape formulas.

- Here There Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles. ↩︎

- The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 1 ↩︎

- Here There Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles. ↩︎

- This is according Emerick’s recollection in Here There Everywhere: My Life Recording The Beatles. ↩︎

- The Beatles Recording Reference Manual: Volume 1 ↩︎